The life story of an ordinary, brilliant, anarchist peasant from Brittany

Exactly 112 years ago, on January 6th 1905, a Breton peasant neamed Jean-Marie Déguignet wrote the last words of the story of his life, and died shortly after. He ended over 4,000 pages with these words : “I wish humanity the power – even the willpower – to become truthfull and good people, able to understand and get along with each other, in a worthy and happy social life.” His own life has been neither happy nor worthy, which is why this best-selling autobiography is such a fascinating account of rural life between 1834 and 1905. I’ll try to make this review worth reading.

“He both suffers and celebrates his suffering as the price of his nonconformity. A fascinating account.” — Alan Riding, New York Times Book Review

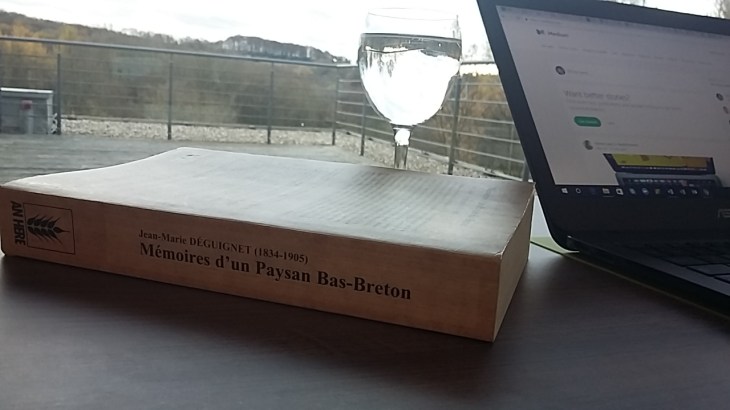

Back then, it was impossible & unthinkable for peasants to write their lives’ stories. They were born and raised to work in the fields, not to travel and write for posterity. Jean-Marie Déguignet started his live miserably too, and nothing predestined him to sell hundreds of thousands of books a century after his death (“Memoirs of a Breton Peasant” was first published in French in 1998). But his extraordinary memory allowed him to recall almost every details of his life, which he wrote down out of boredom and despair in his final years.

Born into rural poverty in 1834, when begging and child work were common and few went to school, Déguignet learned to write in the fields. He never went to school himself, but used a notebook lost by a pupil when visiting the barn in which Déguignet worked as a kid. He set out to learn it by himself.

“As soon as I was in the fields with cows, I took my pencil, a white sheet of paper and I tried to form letters. I quickly found out that it would be more difficult to learn writing that it was to learn reading. My head learned what it heard and saw, but my hand wasn’t as skilled as my head. Used to handling heavy tools, it wasn’t used to handle a pencil.” (translated from French)

It’s by watching the moon and the stars around it that he wondered about astronomy, it’s by reading leftover newspapers that he learned French (he grew up only talking Breton), it’s by looking at his region’s telegraph lines that he became curious about technology… As soon as he was old enough, he set out to see the world and left Brittany by joining the French Army in 1854, aged 20. Over the next 14 years he fought in the Crimean war, attended Napoleon III’s coronation ceremonies, supported Italy’s liberation struggle, and defended emperor Maximilian in Mexico.

During all these years, he met a lot of people and formed his opinion about the world. He was disappointed by Jerusalem (“We didn’t stay long to contemplate this shameful trade, this profanation of nature, common sense and reason“) but seemed satisfied with his condition as a traveller (“To be happy on this tiny globe, all you need is something to eat as well as physical and moral occupations that fit your [faculties]“), despite the toughness of the military at the time. He learned Italian, Spanish and Latin and made friends across the globe; simple people like him.

He eventually returned to Brittany to have a family, live as a farmer and tobacco-seller, falling back into dire poverty. While in Mexico he was close friend of the librarian, in his hometown Quimper the librarian laughed him off because of his appearance. Some excerpts are moving and saddeing, barely scraping the surface of the deep sorrows in which Déguignet must have been at some points of his life. “The French always say: the truth is not allways worth being told. […] No one knows this better than me as I have been a victim all my life, and I have suffered cruelly, for always having told the truth,” he writes in the late pages of the memoirs.

He wrote the diaries because he couldn’t figure out what else to do in his final years, when his children didn’t invite him to their weddings and the property owners wouldn’t lend him land, partly because of his anticlericalism. “In this attic, I killed time by scribbling the story of my life, and when I was tired of writing, I went for a walk by the river.“

His memoirs eventually got translated into English (“Memoirs of a Breton Peasant”) by Linda Asher – a portrait of hers here – and she made it look more like a novel, less like a historical document for academics. “A fascinating document of an extraordinary life, Memoirs of A Breton Peasant reads with the liveliness of a well-plotted novel — albeit one infused with the vigor of an opinionated autodidact from the very lowest level of peasant society,” she writes. It’s true that I read it like a novel, almost like a fiction, but it’s one that is even more interesting as it’s an exact transcription of reality.

She continues: “Brittany during the 19th century was a place seemingly frozen in the Middle Ages, backwards by most French standards; formal education among rural society was either unavailable or dismissed as unnecessary, while the church and local myth defined most people’s reasoning and motivation. Jean-Marie Déguignet is unique not only as a literate Breton peasant, but in his skepticism toward the Church, his interest in science, astronomy and languages, and for his keen — often caustic — observations of the world and people around him.“

His anticlericalism becomes a bit excessive towards the end, but again: this is a peasant sepaking his heart out and affirming his republican values against the mainstream, not a diplomatic style exercise. Déguignet always stood up for his opinions and beliefs: “I would [die] for my ideas and opinions [as] I am convinced that they are the only which, when applied, can give mankind the wellness it deserves during its short path on this globe.“

The Church certainly wasn’t what it is today, many people held the pastor’s word for an absolute truth. Superstition and faith mixed to the extremes, and tolerance for laymen like Déguignet wasn’t normal. Déguignet had a surprisingly tough stance — which he attributed to his superior cognitive capabilities — towards any form of establishment, whether it be clerical, political or economic. He always stood high in front of social pressure.

“Déguignet’s freethinking, almost anarchic views put him ahead of his time and often out of step with his contemporaries.” — Linda Asher, translator of the English version

More than a century after his death, more than a decade after his life story’s publication, the peasant’s story has moved me. In times like ours, we ought to remember that we live in a free society, in which faith is chosen not imposed, opinion diversity is encouraged not laughed at, curiosity is respected not frowned upon. Child work is at its lowest ever in history, poverty too; life expectation is at its highest, global wealth too; the IQ has progressed by almost 30% since Déguignet’s death (see the ‘Flynn effect’ or just look at these charts).

It is a rare testomonial by a simple yet brilliant mind, an account of a time in which only the educated and (therefore) powerful left marks in history. “Unsettling to a contemporary reader is the degree to which knowledge was a matter of misinformation,” says this reviewer from the United States on his blog. Déguignet now has a Wikipedia page, an Amazon page with loads of reviews, the same on GoodReads, even one in the Agricultural History Review. If you read French and are curious to find out more, here‘s what else happened around Déguignet’s work since.

A remarkable destiny. Maybe turned a movie, one day ?

I did appreciate your blog and specially the last one about the poor peasant. I already orderd the book from Amazon.May I suggest another book quite different but in the same spirit: Un enterrement à Ornans written by Jean-Louis Ferrier. This describes how the famous painting by Gustave Courbet is the first representing poor natural people of mid nineteenth, century. It was presented at the Salon in 1851 and is considered as a major step between classical painting and impressionism.

Linda Asher may think Old Brittany “backward” and Déguignet “unique” but my studies of Breton history suggest the contrary.

This is the country that wrote the first trilingual Dictionary, was recording scientific documents before French was ever written, the nation whose laws in the 800s protected peasants from trespass by aristocrats, which in the 11th century produced Peter Abelard, and whose leaders created the first national parliaments (the English Parliament at York in 1089, and the Breton Estates of 1309 which was the first in mainland Europe to include bourgeois and peasants).

When Henry IV of France passed through Vitré, he was astonished at Breton wealth and commented that, were he not already King, he would king to be a commoner in that town.

Plus Jules Verne, great yachtsmen, the stethoscope, Arthur III of Richmond who saved France from the English, made France into a great power, and is commemorated on both sides of the Channel, and Alan Rufus whose countless great feats inspired the legends of King Arthur and envy of whom gave Ermine to the monarchs of Europe.