I was recently in La Fuye, near Hommes, in the centre of France to make a factory tour of Cyfac’s facility for the specialized website B2Bike.com. Aymeric Le Brun, one of the company’s managers, kindly answered my questions and showed me around. Cyfac is one of the last brands to manufacture bicycle frames in France, and the brand’s positionning is the very high-end segment of the market. The company’s philosophy is to produce fully customized products to its customers all over the world. With about 35% of the turnover coming from outside of France, offering good quality customization (mainly over the web) is Cyfac’s biggest challenge.

Tag / cycling

Cyclisme : courir en compétition aux Etats-Unis

Avant de partir aux Etats-Unis (Floride) pour mon semestre académique, j’ai longtemps cherché des informations sur les courses cyclistes et la possibilité de courir en compétition dans le pays de l’Oncle Sam. N’ayant rien trouvé sur le site de la Fédération Française de Cyclisme, ni sur le site d’USA Cycling, je vous donne là quelques informations pour les français (ou autres étrangers) voulant courir aux USA avec une licence étrangère.

- Les catégories

En France, les catégories sont les suivantes, par ordre croissant : Pass’Cyclisme, 3ème catégorie, 2ème catégorie, 1ère catégorie puis élite. Il n’est possible de courir des courses FFC qu’en étant affilié à cette fédération, et donc de faire partie d’une de ces catégories. D’autres possibilités que je me permets de décrire comme des catégories “loisir” existent également, mais il n’est pas possible de courir des courses officielles FFC avec ce type de licence.

Aux Etats-Unis, les catégories de compétiteurs sont très similaires. Par ordre croissant encore : Category 5, category 4, category 3, category 2, category 1 puis pro. Il est courant là-bas de commencer la compétition en “cat.5” et de monter au fur et à mesure que les résultats s’améliorent (et que – donc – les points USA Cycling augmentent). Les “cat.5” et “cat.4” correspondent donc aux Pass’Cyclisme en France, les “cat.3” aux 3ème catégorie etc. Pour un coureur étranger, français dans mon cas, il est donc recommandé de courir dans la catégorie qui est indiquée sur la licence française. Dans mon cas (je suis 2ème catégorie en France), je courrais donc des courses auxquelles les “cat.2” avaient le droit de participer.

L'arrière du peloton cat.3/cat.4 au départ des championnats de Floride 2010 de critérium à Lakeland, FL

Attention, les catégories de VTT (X-Country) sont différentes : elles vont par ordre croissant de category 3 à category 1, jusqu’à pro. Il est possible d’être “cat.1” en VTT et d’être “cat.5” sur route, par exemple, lorsque le coureur est meilleur en VTT que sur la route (c’était le cas d’un coureur que je connais là-bas)

Dites-moi si je me trompe, mais il me semble que cette classification s’applique au pays entier, quel que soit l’état dans lequel on se trouve. Ça paraît logique.

- Les clubs

Pour courir sur les courses labellisées USA Cycling, il est nécessaire de posséder une licence de compétition, qu’elle soit américaine ou étrangère. Les clubs sont, comme en France, affiliés à la fédération nationale USA Cycling et je n’ai pas remarqué de différences majeures avec le système des clubs français. Une petite différence est qu’il n’y a pas de structures équivalentes à nos DN1/DN2, les très bons coureurs se trouvent soit en “cat.1”, soit dans une équipe “domestic pro” comme UnitedHealthCare, JellyBelly, Kenda etc. Il y a aussi les “developement teams” comme Trek-Livestrong-U23 ou Hincapie Developement Team où courent de très bons coureurs juniors et/ou espoirs.

Dans la ville (Pensacola, FL) dans laquelle se trouve l’université (UWF) dans laquelle je suis allé étudier, il y avait deux clubs de compétiteurs : Subaru-TSCyclones (route et VTT) et Weber Sports Racing (route). Ces deux équipes avaient des coureurs de catégories 5 à 2, jeunes et anciens, hommes et femmes. J’ai moi-même couru pour la deuxième équipe, puisque le hasard des rencontre l’a voulu comme-ça, mais j’ai couru aussi avec la très sympathique équipe Subaru. Pour la liste complète des clubs de Floride, cliquez ici.

Comme en France, il existe aussi des clubs plus cyclosportifs qui participent à des courses de bienfaisance ou autres événements cyclistes. A Pensacola, un de ces clubs est celui des West Florida Wheelmen.

- Les courses

Au Sud-Est des Etats-Unis, où j’ai couru, il y principalement 2 types de courses : les “races” et les “rides”.

Ce qui est le plus proche de nos courses FFC en France sont les “races” que l’on peut trouver sur USACycling.org, qui sont soit des critériums, des courses sur circuit ou en ligne, ou des courses par étapes plus ou moins longues. En général, le même événement permet à toutes les catégories de participer, et ce dans différentes course qui regroupent des coureurs de niveau similaire.

Un exemple : le Sunny King Criterium rassemble des coureurs de toutes les catégories, de tous les âges et des deux sexes sur une journée de course dans le centre-ville d’Anniston, dans l’Alabama. Tôt dans la journée il y a les courses pour les jeunes, puis il y a celles des masters, celles des cat.4/cat.5 et cat.2/cat.3, et finalement celles des pro/cat.1 (femmes puis hommes). Un même concurrent peut, s’il le veut, participer à différentes courses le même jour s’il en a le droit. Étant donné que les critériums sont très courts (de 30 minutes pour les cat.4 ou cat.5 à 80 minutes pour les pro/cat.1). Sachez aussi que les frais d’inscription sont assez élevés sur ces courses, souvent plusieurs dizaines de dollars. Les inscriptions se font en ligne via des sites comme SportBaseOnline ou BikeReg.

Les “rides”, quant à eux, sont des cyclosportives rassemblant des coureurs licenciés et non-licenciés. Des exemples là où j’ai couru sont Rouge-Roubaix (Louisiane) ou encore le Cheaha Challenge (Alabama), deux courses assez mythiques dans le sud du pays. Ce sont là deux “century-rides”, ce qui fait référence à la longueur du parcours : 100 miles (autour de 165 km). Le niveau peut être très relevé comme l’était celui de Rouge-Roubaix en 2010, auquel j’ai participé.

- Le niveau

On peut se demander comment est le niveau des courses de l’autre côté de l’atlantique, par rapport au vieux continent (du cyclisme). Et bien j’ai trouvé que les catégories similaires aux nôtres reflétaient bien le niveau des coureurs. Les catégories 4 et 5 rassemblent les débutants et le niveau augmente avec les catégories. Il m’a semblé que les cat.3/cat.2/cat.1 étaient assez équivalentes à nos 3ème, 2ème et 1ère catégories. Par contre, j’ai eu l’impression que les “domestic pro” n’avaient pas le niveau des coureurs d’équipes “continentales pro” en France. J’étais étonné de me retrouver parmi les meilleurs de la Foothills Road Race (le même jour que le Cheaha Challenge) avec les pros, peut-être n’aiment-ils pas les bosses du parcours…

Cela est peut-être lié au fait que les courses étaient courtes et que les américains se spécialisent davantage sur les critériums (courts) que sur les courses en circuit ou en ligne. Je ne suis pas sûr… Pour terminer, j’ai remarqué quelques différences de niveau entre états dans lesquels on a couru : les cyclistes de Géorgie et de Floride du Sud semblent avoir un niveau plus élevé que ceux de l’Alabama ou du Mississippi. Encore une fois, ce n’est qu’un ressenti et cela se limite aux courses auxquelles j’ai participé.

What caused Shimano’s Coasting-program to fail ?

A couple of weeks ago, I noticed that the Coasting-website (coasting.com) was not online anymore and that the landing page was Shimano’s corporate website, Shimano.com. Just before writing this, I googled it again and there is shimanocoasting.com again, on the bottom of the page, just behind the link to my blog post (results may vary from country to country) ! Did I make a mistake, in March, when I was looking for the website ? Did I just miss it ?

But more interestingly, what bugs me is : What caused the Coasting program to fail ?

In a very interesting guest post on BicycleDesign.net, designer Mark Sanders basically talks about the cycling market as bunch of companies which sell high-priced bicycles to enthusiast cyclists (he calls them red oceans of enthusiasts). On the other hand, you have the mass-merchandisers selling very low-priced bikes in chain stores and supermarkets, targeting the mass of shoppers. Since these two approaches make companies compete on very “crowded” markets with low margins, we can indeed talk about red oceans that Kim & Mauborgne’s describe in their theory on business strategy, the Blue Ocean Strategy. In this theory, companies achieve growth by creating innovative ways to satisfy customers’ needs (differentiation), thus avoiding the high costs that incurr in highly competitive markets, and also driving up value for these customers. So is the cycling industry an unattractive industry ? According to Sanders, yes. I also think about an interview (in Institutional Investor of April 2005) of Martin Schwartz, CEO of Dorel Industries that I read when I got interested in Schwinn’s history ; he says that “bikes, it’s true, is not a great industry, but someone has to be the best, and Pacific (bike division of Dorel, ed) is the best by far“. Shimano seemed to having recognized that, and that’s where the industry-giant worked with IDEO, a global design consulting firm, to find a solution : Coasting.

The previous paragraph relates to both the Blue Ocean theory (2005) and the Design Thinking theory (2008) to describe Shimano’s initiative. IDEO is even run by the guy who wrote the HBR-article on Design Thinking, Tim Brown. So Shimano was basically advised by one of the leading strategists in the world, but about 3 years after the lauch of the Coasting product-line, the program was abandoned because it didn’t generate the expected commercial success that Shimano hoped for. The program thrilled the design-community (California Design Biennal Award for Giant in 2007, International Design Excellence Award in 2008), was praised by journalists and commentators (L.A. Times or Cyclingnews.com in 2007), but sales didn’t follow. Why ?

Several reasons cross my mind, and I’d like to have your feedback to contribute to the discussion…

- Design process ?

Shimano’s brief for IDEO was more or less as follows : help it create a $1,000, tech-laden bike that would lure baby boomers and their loose change off the couch (bicycling.com). It is very common in the design process that the consulting firm reformulates this brief, and it indeed proved to be necessary. Aaron Slar, social engineer for IDEO, and David Lawrence, marketing manager for Shimano travelled to different U.S. cities to find out what people think about bikes and biking and discovered all these things about people being intimidated by technology and basically wanting to get the feel-good biking experience they remember from their childhood. The prototype had grinded lugs and cable routers, a coaster brake and, more importantly, an invisible shifting mechanism. When IDEO presented their findings and recommendations to Shimano in Japan, “there was a long pause on the conference call. And it wasn’t just because of the translation“, says Lawrence. But the company rapidly got convinced, and started seeking partners within the industry.

An extract from Tim Brown's HBR-article on Design Thinking. Inspiration, ideation & implementation are represented here by examples

This design process seems to have gone through the traditional steps, from understanding to prototyping and testing. Actually, I found few information about this “testing”-step. Who did Shimano and IDEO work with when they testes their prototype(s) ? Where there improved V2 and/or V3 versions based on customers’ feedback ? This would be interesting to know.

- Industry involvement ?

According to Daniel Gross, manufacturers associated in the Coasting-project (3 in the first year, 10 the year after) were rapidly found and seemed enthusiatic about the idea. Giant adapted bikes from its Suede product-line, Trek & Raleigh created bikes, the Lime and the Coasting. Today, the Shimano Coasting website shows 7 models from 7 different brands : Schwinn, K2, Phat, Fuji and the 3 brands that started with Shimano. I wonder what caused the number of manufacturers to drop ? They were indeed 10 in 2008, why did Sun, Jamis & Electra quit the program ? One possibility is that Shimano could not handle working closely with these 10 manufacturers and needed to skim off the least motivated ones… While some talk about a synergy between this major supplier and manufacturers, I wonder if the manufacturer’s didn’t think that Shimano would get too powerful if Coasting was a success ? Would have one single bike manufacturer have been more successful with the Coasting-approach ?

Shimano’s goal was to get 1,000 U.S. retailers involved the first year. In 2008, two years after the lanch of the group, industry consultant Jay Townley of Gluskin Townley Group said retailers were still hesitant to adopt the new product. To improve this situation, Shimano sent them an explanatory DVD and did set up a dedicated website, sellingcoasting.com. But even this kind of initiatives did not make sales take off. When I talked to a bike dealer here in Pensacola he wasn’t very convinced by the Lime’s (Trek’s Coasting-model) ability to reach a new target of customers. If bike vendors don’t grasp it, the customer probably won’t either…

- Marketing mix ?

PRODUCT : Did the consumer know what was actually sold by Shimano ? The company only sells the transmission and shifting-system by its Coasting group. This product is then mounted on the bikes by manufacturers, who sell the bicycle through independent bicycle dealers (IBD) in the United States. But Coasting is also a concept, a lifestyle, a new way of designing riding experience. I think it was made too hard for the customer to identify what he was actually buying : did he buy a Trek ? a “Coasting” ? a Shimano ? Who made what on this bicycle ? Why change the shifting-system ? I think it was not Shimano’s role to directly adress the customer, it is still the bike brands’ job to sell their products.

PRICE : The 3 initial Coasting bikes sold between 400$ and 700$. The Trek Lime’s retail price was roughly 500$, which is a fair price for a quality bicycle. It is half the price of what Shimano initially suggested to IDEO in the design brief. The aim of this pricing strategy was obviously to make bikes affordable to a large public who doesn’t ride bikes. I think the price was not a reason for failure, it was more that Shimano and, more importantly, the manufacturers were not able to communicate the benefits of Coasting to retailers and customers.

The K2 Easy Roller is (was?) available at 600$. Quite a bit for a bike with no handlebar-brakes (photo from besportier.com)

PROMOTION : The promotional strategy was intended to convey this feeling of freedom of riding a bicycle and to draw non-cyclists to the stores that sold Coasting. Newspaper advertising and guerilla marketing were used to increase awareness of Coasting, and the website Coasting.com was central to explain the concept and present bikes to consumers. The design of this flash-based website is fun and interactive, storytelling is used to involve the visitor (storytelling is part of the Design Thinking process, according to Tim Brown) and content encourages people to get on their bikes. Ideally Coasting bikes. Beside this, a demo-tour was also organized in several U.S.-cities to bring the bikes to the poeple and encourage PR & publicity.

The Fineline used outdoor stencils (with environmentally friendly spray chalk) to create life sized coasting paths everywhere (photo from the-fineline.net)

PLACE : Coasting was intended to the U.S.-market only, and it has been launched in cities like Orlando or Phoenix before the whole country was covered in 2008. Shimano and the bike brands chose to sell their products exclusively at IBDs. I think this is one of the reasons that caused Coasting’s failure : while the website is a good way of presenting the concept/product/bikes, poeple are often unfamiliar with the specialized bike stores and bike-enthusiastic vendors. Why not selling through the web ? Was the reliance on a retailing network so important ? It might have avoided some obstacles too… But more than seeing problems on the U.S. market, I think that Shimano should have tried to introduce Coasting (or a similar technology, with a different marketing approach) into less mature markets like China, India and other emerging countries. Or even (very) mature markets like Scandinavian countries and the Netherlands, where product acceptance might have been higher.

VERDICT ?

The future of Shimano’s Coasting is unclear. On the internet, Coasting.com vanished and ShimanoCoasting.com has appeared, the content is unchanged. As I said in a previous post, the program has been abandoned by Shimano because sales never attained the expected figures. I think there was a huge potential in this approach, and this post explains some points that could have led to Coasting’s deceiving results.

What do you think ? Do you have more informations ? More ideas ?

Shimano and associated bicycle manufacturers drop the Coasting program

I don’t know if you recently visited Coasting.com, the website dedicated to the innovation program initiated by Shimano with several bicycle brands like Giant, Trek, Fuji, K2 and even Schwinn (2008). Developped with the innovation firm IDEO, this project intended to bring new consumers to cycling, those who didn’t identify themselves with the technology-driven world of copmetitive cycling. Well, the website now directly brings you to Shimano’s corporate website, Shimano.com.

After contacting Shimano, I found out the whole program had been abandoned – or at least temporarilly stopped. According the Shimano France‘s Mathieu Arrambourg, who was the first to answer my questions, the marketing efforts didn’t generate the expected sales, revealing that customers (and distributors?) were not interested enough in the products. The program, which was exclusively directed to the Northern American market, started in 2007 with Giant, Trek and Raleigh, seven other manufacturers joined the movement in 2008. Heather Abraham from Trek told me that the Lime, Trek’s Coasting model, “is no longer being produced” and that, at this time “nothing new is happening with the Coasting program“.

Shimano rolled-out the program across North America, this is a photo from one of Shimano's Coasting Tour stages in Portland (retrieved from http://www.momentumplanet.com/blog/glorious/north-americas-1st-ciclov)

The Californian headquarters of Giant and Shimano USA haven’t made any statement yet. I understood that the announcement was made to Coasting’s member companies during Taiwan’s Taipei Cycle trade show, and that product managers and other marketing executives couldn not yet communicate on the issue. What ever the statements will look like, I hope that this promising approach of cycling’s marketing won’t be definitively abandonned, because it had (has!) market potential. Imagine what potential there would be in emerging markets like india and China… Or do they really just want cheap cars ?

Feel free to comment or to react !

No hands: The rise and fall of the Schwinn Bicycles Company: an American institution, Judith Crown & Glenn Coleman, Henry Holt&Co.

When I arrived in Florida in early January I noticed all these Schwinn-bikes on campus, in the gym and in the supermarkets. This aroused my curiosity about this brand I already heard of, but who still was misterious to me ; that’s why I lended No Hands: The rise and fall of the Schwinn Bicycle Company: an American institution in the UWF Library. And here’s what I learned in the book, that was published in 1996 (and therefore does not cover Schwinn’s most recent history).

Judith Crown, who is a senior correspondent for BusinessWeek in Chicago and worked for Crain’s Chicago Business, started the book in 1992 after she heard that Schwinn was in serious financial trouble. With Glenn Coleman from Crain’s New York Business, they started investigating the reasons for the turmoil of America’s most notorious cycling brand.

Ignaz Schwinn, co-founder of Arnold, Schwinn & Company (retrieved from http://www.motorcyclemuseum.org)

Ignaz Schwinn emigrated to the United States in 1891 and make profit from the late XIXth century’s bicycle boom to create a successful bicycle manufacturing company with an American partner, the Arnold, Schwinn & Co. The turn of the century and the start of the automotive era (Ernest Pfennig bought the first Ford T in 1903) saw a wave of consolidations in the bicycle business, out of which Schwinn emerged weakened – but even more ambitious. Various takeover made Schwinn one on the big players, and retailing through mass merchants allowed the Chicago-based company to achieve big sales. In 1928, the in-house brand for motorcycles that had been acquired in 1912 and 1917, Excelsior-Henderson, even ranked 3rd in the national motorcycle industry.

This advertisement for Schwinn's Sting-Ray is from 1963 (retrieved from http://www.raleighronsclassics.com)

During the following decades, Schwinn built up a (very) strong brand. The best example certainly is the success of the Sting-Ray that originated from the Californian kids’ street culture (at that time, Schwinn listened to its customers…). Sociologist Arthur Asa Berger saw it in a bit more, let’s say, austere way : “[the Sting-Ray] symbolizes a perversion of values, a somewhat monstruous application of merchandising and salesmanship that… has led to grave distortions in American society“. His vision may be exagerated, but what he said about Schwinn’s marketing efforts gets to the heart of the company’s success : they mastered selective distribution and franchising better than any other consumer product company at the time. Furthermore, Schwinn’s “customers around the country were true believers“, as the book states on page 75, and owning a Schwinn was considered a status symbol in the 60’s.

The mountain-bike pioneers started on converted Schwinns, recognize the frame ? (retrieved from sanfrancisco.about.com)

In the 70’s, Soutern California kids started following new trends (the BMX), just like the kids created the Sting-Ray culture during the sixties. This time, however, Schwinn decided not to engage into the movement, maily because the company saw the sport as too dangerous and unsuitable with Schwinn’s quality image. The same happened with the mountain-bike culture of the 80’s pioneered by Northern California riders like Michael Sinyard (founder of Specialized), Tom Ritchey and Gary Fisher. What Schwinn didn’t recognize is that trends are often set by minority thinkers, and not by the Number One.

In 1988, Giant Manufacturing produced 82% of Schwinn's bicycles, nowadays it is the world's leading bicycle manufacturer (retrieved from http://www.bike-eu.com)

But what eventually drove Schwinn into the turmoil that led the company to file for Chapter 11 in 1992 was it’s inability to cope with management and quality problems, as well as some unsuccessful investments. Basically, the company had to choose in where to produce bicycles at a more competitive prices. The Schwinns decided to turn to Taiwan and China, but even though suppliers like Tony Lo’s Giant Manufacturing (photo) made high quality products, unlucky sourcing desisions led to supply shortage, angry retailers and receding customers. Edward Schwinn, CEO, just wasn’t as passionate about bicycles as his ancestors were. Yoshi Shimano, who was Edward Schwinn’s personal translator during his business trips to Asia, described him as “a nice fellow“, who “had a lower degree of interest for the business“.

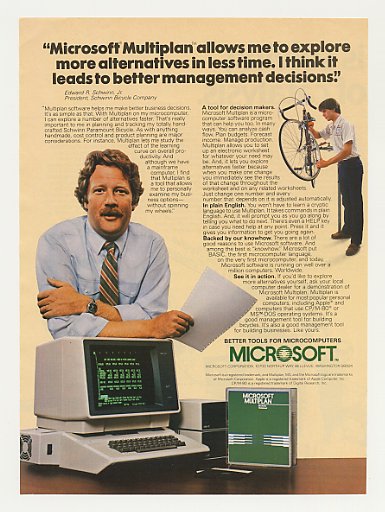

If only Microsoft had helped Schwinn taking better strategic decisions... (advertisement from 1982, retrieved from aroundme.fr)

In 1992, Schwinn filed for bankruptcy. Ed Schwinn looked for an investor during the difficult years that preceded this sad ending, but this reveals a part of the problem : instead of an investor that would provide funds to keep the business running, Ed Schwinn should have found a buyer, which implies that this buyer would have taken control of the company – what the Schwinns wouldn’t accept. When the company was too damaged to be saved, the company and name were sold to the Zell/Chilmark Fund, an investment group, in 1993.

To conclude, let me just quote very hard words that Judith Crown writes about Ed Schwinn, in the introduction of the book : “Most of all, it is a tale of a young CEO who alienated just about everyone he needed – from relatives, employees, and longtime dealers to lenders, lawyers, suppliers and bidders – with a mix of arrogance and ignorance that only can be described as hubris“

He now runs a cheese shop in Wisconsin, so he certainly won’t destroy another American institution !

Cycleurope refreshes traditional brands Gitane & Peugeot

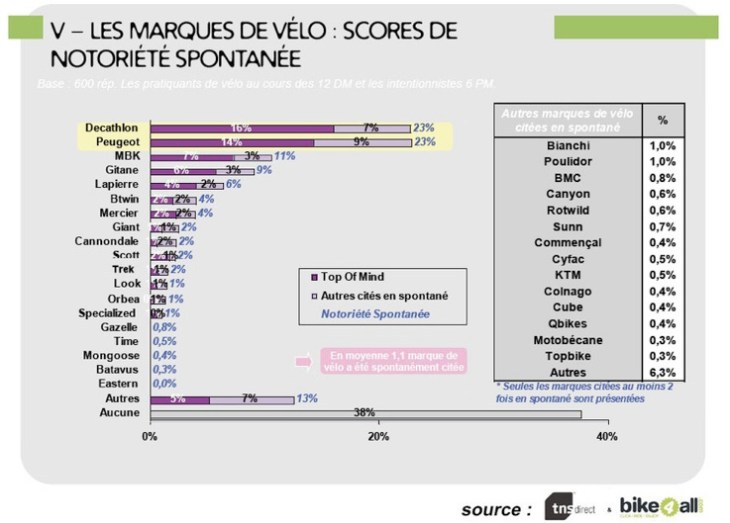

As a survey led in 2008 by TNSDirect for bike4all.com, and related by B2BIKE.com, shows, bicycle brands like Peugeot and Gitane are (still) top-of-mind brands in France. Although these brands stopped selling bikes for several years now, these “traditional” names are quoted by a lot of Frenchmen, one of the reasons might be that Poulidor, Mercier and even Gitane-bikes are sold at very cheap prices in French supermarkets.

As the previous histogram shows, brands which don’t exist anymore are very often quoted by the interviewees : Decathlon nowadays sells bikes under the brands B’twin (6th position) and Rockrider (not quoted), Peugeot has marginal bicycle sales and is distributed by about 40 authorized Peugeot-dealers, Gitane and Mercier are currently cheap supermarket bikes and Motobecane doesn’t exist since 1984 at all (the brand MBK survived to Motobécane’s bankruptcy and as a fair spontaneous notoriety).

Even though it reveals that the French bicycle market offers a huge number of brands and that consumers seem to be lost within that abundant offer, Cycleurope tackles this issue in a quite courageous way : they bet on the revival of these brands ! Strengthened by the notoriety of Gitane and Peugeot, and fairly aware of the asset that it represents, the Grimaldi Group (owner of Cycleurope, which already runs brands like Bianchi and Monark) decide to take the plunge and awake Gitane and Peugeot (at the request of Peugeot Cars HQs). The existing Gitane range will indeed be expanded with a top-of-the-range brand called Definitive Gitane, and Peugeot will extent its distribution network and eventually launch a Peugeot e-Bike.

"The One" bike that Definitive Gitane provides to the Saur-Sojasun team. Gorgeous. (photo from http://www.saur-sojasun.com/goodies.php)

To give credit to Gitane’s revival, Cycleurope Industries developped an additional range of high-performance bikes that meet the competitor’s expectations : cross-country hardtrails and fullies in the MTB-segment, a small range of road bikes topped by “The One“, on which the pro-riders from Saur-Sojasun will compete in 2010. Smaller partnerships were announced like the creation of the French Team ASPTT Definitive Gitane on the national MTB stage.

The Peugeot A2B hybrid bike (in blue) developped with Ultra Motor (about 2300€). Retrieved on January 11th 2009 from jepedale.com

Peugeot bikes (the car manufacturer recently unveiled a new logo) will be manufactured in the French factory of Romilly/Seine and will be sold by Cycleurope, as Toni Grimaldi told Bike Europe a couple of days ago at the official launch of Peugeot Bikes, and they will be distributed both in Cycleurope’s dealer-network (France and abroad) and via Peugeot car dealers, although I guess that’s not the distribution channel that brings them the highest number of sales… The range will include a road racer, a mountainbike, a hybrid/trekking and a city bike which will all be painted black&white. As Peugeot now pushes into the market of electric vehicles, they announced the development of an e-Bike with the Amercians from Ultra Motor.

The move is courageous but clever : two brands with a very high awareness among – at least France’s – cyclists make a credible comeback on the front stage. I’ll certainly be watching the Definitive Gitane bikes on the roads at pro races, Peugeot may gain significant market share by flooding Velo & Oxygen-stores in France and Peugeot-dealers worldwide with their tiny bicycle range. Good luck !

Shimano Coasting, design-thinking applied to the cycling industry

I’m just reading Tim Brown’s article on design-thinking in the Harvard Business Review on June 08, and having a complicated mind, I’m thinking of another subject I love : cycling. In a year-or-so, I’ll have to write my Master and I’m desperately trying to find a way to associate these two passions of mine. Actually, I haven’t found the answer to that very question, but IDEO‘s founder’s article gave me a pleasant surprise that will postpone my reading… just until I finish this post ! An example given by the father of design-thinking to back up his reasoning is the “Coasting”-project led by Shimano since 2004, but let’s come back on it in sequence.

Shimano is world-famous for manufacturing bicycle components, especially shifting and transmission systems (like its competitor, SRAM). By sponsoring numerous professional teams around the world and being official supplier of the UCI, the japanese company proves his leadership in the sector. High-end segments in both road-racing and mountain-bike segments provides solid growth, what leads Shimano to think about the development of a product for a “high-end casual bike“. IDEO is asked to collaborate on the project.

During the first phase of the design-thinking process praised by Brown (Inspiration, Ideation and Implementation), the stakeholders realize that it would be smarter to target a larger audience than the tech-freaks who would by an expensive commuting bike. The reasons are simple : they discovered that a lot of Americans are “intimidated by cycling“, the reasons being various (roads, technology, culture etc.). Long story short, Shimano decided to tackle this problem by proposing “a whole new category of bicycling [that] might be able to reconnect American consumers to their experiences […] while also dealing with the root causes of their feelings of intimidation“. The concept Coasting was born.

You can find an extensive case study of the project on IDEO’s website, but basically Coasting means that the bike is simple and fun to ride, user friendly and technologies like the automoatic shifting are well-hidden. Branding was built on enjoying life on a bike and promotion was partly based on public relations (local governments, cycling organizations) that promoted safe and easy riding for everyone. At the begining (launch in 2007), only three major manufacturers decided to follow Shimano on the coast path : Giant, Raleigh Bicycles and Trek Bikes.

On Shimano North-America’s website, where the above picture is taken from, there are ten manufacturers listed for the 2008 launch of the Coasting Bikes, Trek being one of them. On the current website of the Coasting project, there are still 7 : Giant, K2 (my bike brand!), Phat Bicycles, Raleigh, Schwinn, Trek and Fuji. However, the idea of designing futuristic but simple-looking cruisers for the masses (at a price of USD 700!) worked : Coasting won the Gold Idea Award for Design Exclellence (Industrial Designers Society of America and BusinessWeek) in 2008 and earned a lot of applause since. Brands like Cannondale are thinking about developping similar concepts, as this “concept-bike” by Dutch industrial designer Wytze Van Mansum shows.