Yesterday, the Design & Innovation club of the ESSCA-Alumni invited Philippe Picaud, VP of Design of the world’s second-largest retailer Carrefour, to speak about his experience and the role of design in corporate strategy. The speaker is learned designer, and highlights that “in the 70’s, designers were not meant to stay within corporation“. He did. He took on more and more design responsabilities in companies such as Texas Instruments, Philips or the French sports retailer Decathlon, which he morphed “from a retail-company to a brands-company“. It’s his fault if Decathlon is the only credible and innovative sports vendors in France! 😉 Continue reading →

Tag / brand

L’émergence des marques de communauté (et pas l’inverse!)

Aujourd’hui, il existe de plus en plus de communautés de marques. Certaines sont anciennes (Harley-Davidson), d’autres sont plus récentes dans l’histoire d’une marque (Nutella). Certaines représentent la quasi-totalité du capital de l’entreprise (Warhammer), et d’autres sont beaucoup plus périphériques et marginales (Orange). Le point commun entre toutes ces communautés, cependant, est qu’elles sont créées et exploitées à des fins commerciales, et la majorité des consommateurs en sont bien conscients (et ils jouent le jeu s’ils y voient un intérêt). Dans l’excellent livre Marketing critique: le consommateur collaborateur en question, j’ai cependant découvert un concept nouveau : la marque de communauté. Des exemples ? Continue reading →

eYeka, ou comment créer directement avec les marques

Avant de vous souhaiter une bonne année 2011, je tiens à annoncer que je vais effectuer mon stage de fin d’études en tant que stagiaire chez eYeka, la plus grande communauté mondiale dédiée à la co-création. J’y intègrerai le département Sales Marketing – mais qu’est-ce que la co-création ? “La co-création consiste, pour une entreprise, à développer des produits ou services en collaboration active avec ses clients et ce, de façon durable“, nous dit Wikipedia. Continue reading →

Flipped: How bottom-up co-creation is replacing top-down innovation, John Winsor

I just finished this little book written by John Winsor, and as accustomed I’m sharing my thoughts about it. M. Winsor is the co-founder and CEO of the ad agency Victors & Spoils, the first agency built on crowdsourcing principles. In this short book, he tells us how businesses can benefit from co-creation in marketing and innovation, and details the seven steps that allow them to embrace a beneficial bottom-up strategy.

“If I had asked my customers what they wanted, they would have said a faster horse” Henry Ford

What John Winsor calls a “bottom-up” is the fact that companies should get into a relationship with their customers before the launch of a product, not after it. But more than asking people what they want, this relationship is more about “intimately knowing the customers at the front end of the process“, says Winsor. I won’t give the seven steps that he advises companies to build up to co-create from the bottom-up because (1) it would be boring, and (2) it’s what the whole book is about. Let me highlight some examples that are used to illustrate strategies of bottom-up co-creation. Continue reading →

Le crowdsourcing dans la communication: portrait de l’agence parisienne Creads

Cette semaine, la SNCF a lancé une grande opération de crowdsourcing: avec le concours Les Français Vus Du Train, elle vise à faire participer les consommateurs, en leur faisant connaître l’exposition SNCF qui se tient actuellement aux Jardins du Luxembourg à Paris. L’agence qui se cache derrière cette action de communication site web s’appelle Creads, et se positionne comme la première et l’unique agence de communication participative en France. Aujourd’hui présente à Paris, Tokyo et à Barcelone, Creads compte des grandes marques parmi ses références: Areva, Bouygues Telecom, Decathlon ou Société Générale. L’un des fondateurs, Julien Mechin a eu la gentillesse de me présenter son l’agence, qui joue à fond la carte du crowdsourcing communautaire. Continue reading →

Finding the Sweet Spot through customization : French bicycle manufacturer Cyfac International

I was recently in La Fuye, near Hommes, in the centre of France to make a factory tour of Cyfac’s facility for the specialized website B2Bike.com. Aymeric Le Brun, one of the company’s managers, kindly answered my questions and showed me around. Cyfac is one of the last brands to manufacture bicycle frames in France, and the brand’s positionning is the very high-end segment of the market. The company’s philosophy is to produce fully customized products to its customers all over the world. With about 35% of the turnover coming from outside of France, offering good quality customization (mainly over the web) is Cyfac’s biggest challenge.

No hands: The rise and fall of the Schwinn Bicycles Company: an American institution, Judith Crown & Glenn Coleman, Henry Holt&Co.

When I arrived in Florida in early January I noticed all these Schwinn-bikes on campus, in the gym and in the supermarkets. This aroused my curiosity about this brand I already heard of, but who still was misterious to me ; that’s why I lended No Hands: The rise and fall of the Schwinn Bicycle Company: an American institution in the UWF Library. And here’s what I learned in the book, that was published in 1996 (and therefore does not cover Schwinn’s most recent history).

Judith Crown, who is a senior correspondent for BusinessWeek in Chicago and worked for Crain’s Chicago Business, started the book in 1992 after she heard that Schwinn was in serious financial trouble. With Glenn Coleman from Crain’s New York Business, they started investigating the reasons for the turmoil of America’s most notorious cycling brand.

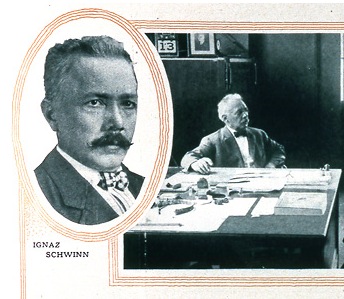

Ignaz Schwinn, co-founder of Arnold, Schwinn & Company (retrieved from http://www.motorcyclemuseum.org)

Ignaz Schwinn emigrated to the United States in 1891 and make profit from the late XIXth century’s bicycle boom to create a successful bicycle manufacturing company with an American partner, the Arnold, Schwinn & Co. The turn of the century and the start of the automotive era (Ernest Pfennig bought the first Ford T in 1903) saw a wave of consolidations in the bicycle business, out of which Schwinn emerged weakened – but even more ambitious. Various takeover made Schwinn one on the big players, and retailing through mass merchants allowed the Chicago-based company to achieve big sales. In 1928, the in-house brand for motorcycles that had been acquired in 1912 and 1917, Excelsior-Henderson, even ranked 3rd in the national motorcycle industry.

This advertisement for Schwinn's Sting-Ray is from 1963 (retrieved from http://www.raleighronsclassics.com)

During the following decades, Schwinn built up a (very) strong brand. The best example certainly is the success of the Sting-Ray that originated from the Californian kids’ street culture (at that time, Schwinn listened to its customers…). Sociologist Arthur Asa Berger saw it in a bit more, let’s say, austere way : “[the Sting-Ray] symbolizes a perversion of values, a somewhat monstruous application of merchandising and salesmanship that… has led to grave distortions in American society“. His vision may be exagerated, but what he said about Schwinn’s marketing efforts gets to the heart of the company’s success : they mastered selective distribution and franchising better than any other consumer product company at the time. Furthermore, Schwinn’s “customers around the country were true believers“, as the book states on page 75, and owning a Schwinn was considered a status symbol in the 60’s.

The mountain-bike pioneers started on converted Schwinns, recognize the frame ? (retrieved from sanfrancisco.about.com)

In the 70’s, Soutern California kids started following new trends (the BMX), just like the kids created the Sting-Ray culture during the sixties. This time, however, Schwinn decided not to engage into the movement, maily because the company saw the sport as too dangerous and unsuitable with Schwinn’s quality image. The same happened with the mountain-bike culture of the 80’s pioneered by Northern California riders like Michael Sinyard (founder of Specialized), Tom Ritchey and Gary Fisher. What Schwinn didn’t recognize is that trends are often set by minority thinkers, and not by the Number One.

In 1988, Giant Manufacturing produced 82% of Schwinn's bicycles, nowadays it is the world's leading bicycle manufacturer (retrieved from http://www.bike-eu.com)

But what eventually drove Schwinn into the turmoil that led the company to file for Chapter 11 in 1992 was it’s inability to cope with management and quality problems, as well as some unsuccessful investments. Basically, the company had to choose in where to produce bicycles at a more competitive prices. The Schwinns decided to turn to Taiwan and China, but even though suppliers like Tony Lo’s Giant Manufacturing (photo) made high quality products, unlucky sourcing desisions led to supply shortage, angry retailers and receding customers. Edward Schwinn, CEO, just wasn’t as passionate about bicycles as his ancestors were. Yoshi Shimano, who was Edward Schwinn’s personal translator during his business trips to Asia, described him as “a nice fellow“, who “had a lower degree of interest for the business“.

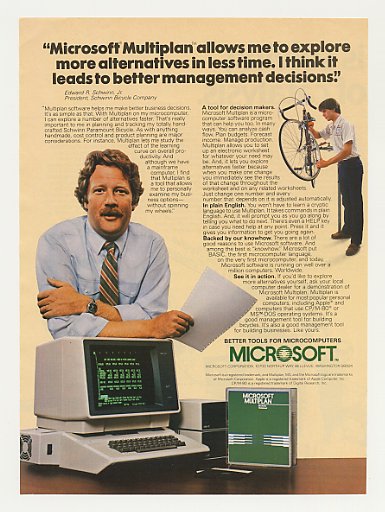

If only Microsoft had helped Schwinn taking better strategic decisions... (advertisement from 1982, retrieved from aroundme.fr)

In 1992, Schwinn filed for bankruptcy. Ed Schwinn looked for an investor during the difficult years that preceded this sad ending, but this reveals a part of the problem : instead of an investor that would provide funds to keep the business running, Ed Schwinn should have found a buyer, which implies that this buyer would have taken control of the company – what the Schwinns wouldn’t accept. When the company was too damaged to be saved, the company and name were sold to the Zell/Chilmark Fund, an investment group, in 1993.

To conclude, let me just quote very hard words that Judith Crown writes about Ed Schwinn, in the introduction of the book : “Most of all, it is a tale of a young CEO who alienated just about everyone he needed – from relatives, employees, and longtime dealers to lenders, lawyers, suppliers and bidders – with a mix of arrogance and ignorance that only can be described as hubris“

He now runs a cheese shop in Wisconsin, so he certainly won’t destroy another American institution !